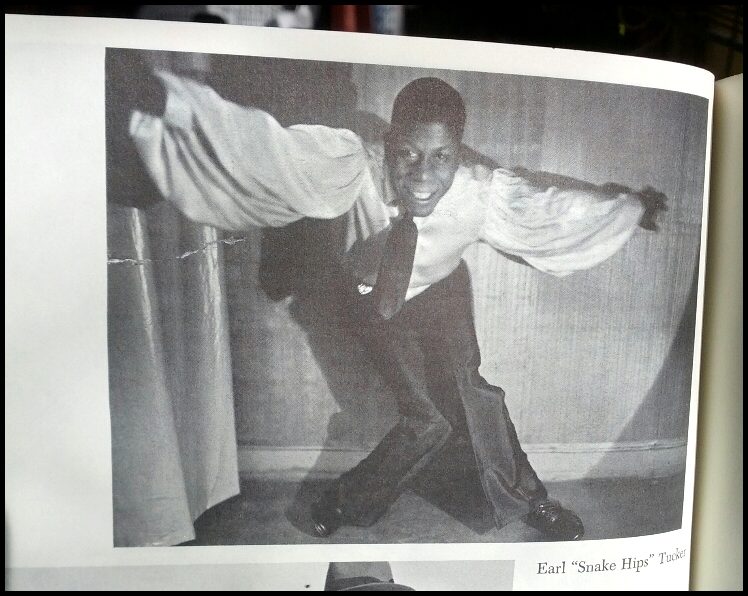

(Part Four - The Song Writer: Perry Bradford-I)In the photo section of the book, "Snake Hips" (below) does appear to be doing something with his knees and feet very reminiscent of Elvis, while bent over from the waist with his arms outstretched and a mischievous expression on his face. (If in fact he's also doing a "figure-8" of the hips at the same time, that's a new one on me - I'll have to try it!)

"The evidence for the earlier appearance [prior to 1916] of the Shimmy in the South is overwhelming. Wilbur Sweatman thought the name had been coined around 1900 by the legendary New Orleans pianist, Tony Jackson. Coot Grant saw it in a Birmingham honky-tonk in 1901; Perry Bradford says, 'In Atlanta they called it the Shake, and I saw it for several years before 1909, when I put it into "Bull Frog Hop"'; dancer Nettie Compton says, 'We did the shimmy in San Francisco in 1910 and later called it the Shimme-Sha-Wobble - most dancers put a tremble in it and some shook everything, but I never exaggerated those things'; and Spencer Williams finally capitalized on its popularity by incorporating the dance into a dance-song called 'The Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble' in 1917: 'I can't play no piano, can't sing no blues, but I can Shim-me-sha-wabble from my head to my shoes.'"(Part Seven - Specialties: Eccentric Dancing)

"The Shake dance, another specialty that qualifies as eccentric and even contortionist (among other things), traces back at least as far as the "Egyptian" belly dance and the Afro-American Grind, although it surfaced in varying times and surroundings. As performed by Little Egypt at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, where it first received national attention as the Hootchy-Kootchy, the Shake dance was not particularly rhythmic. (George Walker's wife, Ada Overton, was the only Negro on the big time to have her own version of a Salome Dance - around 1910 - with a special string section added to Creatore's band.)

"By the twenties and later in various revues and night clubs, such women dancers as Ola Jones, Louise "Jota" Cook ('What she did with her stomach,' says trumpeter Ray Nance, 'would make you seasick'), Kalua, Bessie Dudley, Princess Aurelia, and Tondelayo were synchronizing their undulations to jazz rhythms. 'Every chorus line had some kind of a shake dancer,' says Mae Barnes, 'from The Whitman Sisters on T.O.B.A. [Theatre Owners Booking Association] to Florence Mills who shook in Dixie to Broadway.'""The Shake began as a woman's dance, in the European tradition, but a few male dancers born and raised in the South gradually developed their own parallels to it."

"In the mid-twenties Earl Tucker ("Snake Hips") arrived in New York from the May Kemp show in Baltimore and blew the whistle. 'I think he came from tidewater Maryland,' says Duke Ellington, who employed Tucker to go with the band's jungle effects, 'one of those primitive lost colonies where they practice pagan rituals and their dancing style evolved from religious seizures.'"

"Snake Hips became a fixture in the show at Connie's Inn, dancing at the Cotton Club later to Ellington's 'East St. Louis Toodle-Oo.' (Ellington also composed the 'Snake Hips Dance' for him.) He wore a loose white silk blouse with large puffed sleeves, tight black pants with bell bottoms, and a sequined girdle with a sparkling buckle in the center from which hung a large tassel. Tucker had at the same time a disengaged and a menacing air, like a sleeping volcano, which seemed to give audiences the feeling that he was a cobra and they were mice."

"When Snake Hips slithered on stage, the audience quieted down immediately. Nobody snickered at him, in spite of the mounting tension, no matter how nervous or embarrassed one might be. The glaring eyes burning in the pock-marked face looked directly at and through the audience, with dreamy and impartial hostility. Snake Hips seemed to be coiled, ready to strike.

"Tucker's act usually consisted of five parts. He came slipping on with a sliding, forward step and just a hint of hip movement. The combination was part of a routine known in Harlem as Spanking the Baby, and in a strange but logical fashion, established the theme of his dance. Using shock tactics, he then went directly into the basic Snake Hips movements, which he paced superbly, starting out innocently enough, with one knee crossing over behind the other, while the toe of one foot touched the arch of the other. At first, it looked simultaneously pigeon-toed and knock-kneed.

"Gradually, however, as the shining buckle threw rays in larger circles, the fact that the pelvis and the whole torso were becoming increasingly involved in the movement was unavoidably clear. As he progressed, Tucker's footwork became flatter, rooted more firmly to the floor, while his hips described wider and wider circles, until he seemed to be throwing his hips alternately out of joint to the melodic accents of the music.""The next movement was known among dancers as the Belly Roll, and consisted of a series of waves rolling from pelvis to chest - a standard part of a Shake dancer's routine, which Tucker varied by coming to a stop, transfixing the audience with a baleful, hypnotic stare, and twirling his long tassel in time with the music.

"After this Tucker raised his right arm to his eyes, at first as if embarrassed (a feeling that many in the audience shared), and then, as if racked with sobs, he went into the Tremble, which shook him savagely and rapidly from head to foot. As he turned his back to the audience to display the over-all trembling more effectively, Tucker looked like a murderously naughty boy. The impression he gave was apparently intentional, for he appealed particularly to women, and by all reports, knew it. 'Few men could move like that,' says dancer Al Minns who can do a Snake Hips of his own. 'Women were fascinated and even wanted to mother him.'""Tucker has been described as the first male headliner who did not tap - which does him less than justice. (He could do a tap Charleston.) 'I don't think we would have had the nerve to do that kind of dancing in my time,' says Willie Covan."

"Tucker's fantastic skill at pelvic movements was too early and convincing to influence the general surfacing of this element in vernacular dance. (In the film short 'Rhapsody in Black,' with Duke Ellington, Earl Tucker appears briefly, but long enough to cause consternation among current viewers who can take Elvis Presley in stride.)"

The book follows the evolution of "jazz" dance through the '60's, put together by means of dozens of interviews, and includes extensive footnotes, a bibliography, a list of movies and kinescopes (from the really early days) that feature jazz dance, and even a section of labanotation of various steps and dances, complete with its own glossary! (Will this be required knowledge if and when we finally agree on a standardization of terms for our dance?)

I was surprised at how interesting I found this book, since I don't find modern dance or today's jazz dance very sympathetic; however, this book does make a distinction between the "old" style of jazz dance and the new "Euro-American" form. I found the parallels between the movements of slave-derivative dances and Oriental dance very interesting. It may be out of print now, but at just twenty years old and a classic at that, it shouldn't be too hard to find.